Busted: A Metaphysical Murder in Chicago

Back in 1877, a publication known as the Religio-Philosophical Journal kept an eye on all things Spiritualism. With around 10,000 subscribers, the weekly periodical was founded in Chicago on 1865 by Stephen S. Jones. The press was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1871, yet despite the heavy financial loss, Jones resurrected the journal from the ashes quite literally.

In its heyday, Spiritualism itself swept across the nation like wildfire. What began by all accounts with the Fox Sisters communicating with the dead became a bustling religion based on spirit communication. Even the wealthy and powerful were caught up in its charms. And where there’s money to be made, dubious characters are bound to sneak in for a piece of the action. Even so, the Religio-Philosophical Journal focused on what was believed to be genuine phenomena and upstanding mediums.

Jones was a Universalist who had served as a lawyer in Chicago’s Hyde Park and a judge for Kane County before a chance reading of Nature’s Divine Revelations, and a Voice to Mankind by medium Andrew Jackson Davis sent him on his journey into Spiritualism. It became his new obsession, culminating in the purchase of a printing press and office on Dearborn Street in downtown Chicago where he created the Religio-Philosophical Journal and printed its first issue on August 26, 1865. The Great Chicago Fire destroyed everything, and the insurance company refused his claim, but with the help of loans he rebuilt his press at 127 4th Avenue. It seemed that Jones could survive anything, but his generosity and one fateful tenant would lead to his own demise.

Described by one New York Herald reporter as “a cadaverous-looking man of sixty-five years of age, who looks like a maniac”, William C. Pike called himself a “professional psychologist”, physiologist, phrenologist, “teacher”, and many other various things. Born in Elgin, Illinios, Pike lived in New York working as a phrenologist before moving to Illinois with his wife, spiritual medium Genevieve Evans. The pair began renting a room from Stephen Jones in October of 1876, though the term “renting” implies Pike actually paid any rent. By March 1877, Pike owed $28 in late rent. When Jones discovered that Pike had been paying rent at another apartment elsewhere in the city, he told Pike it was time to pay up in full. Pike only paid him $4.

ADVERTISEMENT

On March 15, Pike had dismissed the thought of the owed money and instead became obsessed with a belief that Jones had been making indecent remarks to his wife and proclaiming his love for her. Allegedly, another woman named “Mrs. Robinson” tipped off Pike to the affair. Filled with rage and jealous insanity, he made his wife sign a letter of confession:

Do you Genevieve Pike, solemnly swear, in the name and presence of Almighty God and His loving son Jesus Christ, in whom you trust for salvation, that the revelations and statements made to me in your confession respecting S. S. Jones are all true; that without provocation or intention on your part, while professing friendship to me, knowing you to be my lawful wife, he did treacherously, by falsehood, fraud and force mislead you and seduce you, making you believe that you were the only woman he loved, and do you solemnly swear that he is the only man with whom you have ever sinned?

I do. It is all true, so help me God.

GENEVIEVE PIKE.

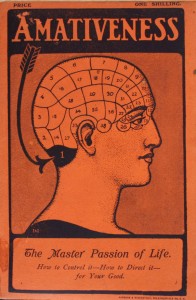

Armed with the note and a Smith & Wesson Model 1 revolver, Pike strolled into Jones’ office and showed him the signed confession. Exactly what happened after that moment is uncertain, but within moments, Pike pulled out the revolver and shot Stephen Jones twice at close range. According to Pike’s own admission, the first bullet entered Jones’ skull at the base behind the ear. “I shot him according to phrenological reasoning in the offending part, the main nerve that comes near the surface at the immediate base of the brain, a little to the right of the spinal column. It also happened to be a most fatal spot.” In phrenology, this spot is referred to as the amativeness and is tied to “connubial love”, obscenity, and the attraction between the sexes. The second shot—just for good measure—entered Jones in the shoulder.

Having done what he apparently set out to do, Pike strolled down to the Harrison Street Police Station and walked inside at 2:03 PM. He was met by two officers.

“I came here to give myself up,” Pike proclaimed nonchalantly.

“For what?” replied stationkeeper Max Ripley.

“I’ve shot a man.”

“Who for God’s sake?”

“Stephen S. Jones, editor of the Religio-Philosophical Journal on Fourth Avenue.”

“Did you really shoot him—kill him?”

“Well, I don’t know that he is dead; but if you go down there you’ll find his body, either dead or alive. He seduced my wife, and I shot him twice for it. Here’s the pistol I did it with,” Pike stated, handing over the revolver. He was immediately placed into custody.

What followed was a sensational trial followed closely by the Chicago Tribune. As expected, Pike went for an insanity defense and entered court representing himself. If he was trying to look insane, he certainly succeeded. A reporter in the courtroom described the accused: “Pike’s clothing would honestly have disgraced a scare-crow. A single-breasted frock coat with two buttons and any quantity of pins on the front, fastened up to his neck; his hair and beard, grizzled and gray, did away with the necessity for collar or tie; rusty black pantaloons, dilapidated shoes, and a hat greasy and napless from long service, completed all that was visible of a garb which would have been grotesque but for the ghoulish, silent aspect of the wearer.” Pike refused all questions while on the stand, as did Genevieve who broke down several times and refused to speak about the signed confession.

The majority of the facts surrounding the case came out during questioning of police officers who spoke with Pike as well as friends and business associated of Jones, who all painted a picture of Jones as a loving husband and family man hardly likely to be making passes at another woman. On the other hand, Pike’s character didn’t hold up well under close scrutiny. On the stand, Genevieve admitted knowledge of her husband’s mental frailty. She told the court, “In 1870 my husband was shut up in the lunatic asylum in Taunton, Massachusetts, and in 1871 he was twice in a New York bedlam [called Blackwell’s Island, a poorhouse and pauper’s lunatic asylum].” Then on March 18th, the Chicago Tribune uncovered the story behind Genevieve, whom Pike met while under the alias of Dr. William C. P. Robinson, a practicing phrenologist in St. Louis, MO. At that time, he was still married to a woman in Wisconsin though he had walked out on her some time before this. They were an ill-matched pair, both prone to hot tempers and unsupported jealous accusations.

It took the jury only twenty minutes to reach their verdict. William Pike was found guilty of murder in the first degree. Genevieve was held as an accessory to the crime, yet what happened to her is unknown. Pike was sent to a mental hospital for good.

With the death of the Religio-Philosophical Journal’s publisher and founder, the publication was turned over to his son-in-law and business partner, Lieutenant Colonel John C. Bundy. A veteran of the Civil War, Bundy was certainly a Spiritualist and believed in what we would call “paranormal claims”, but he called his beliefs “Rational Spiritualism”—that is, relying on scientific validation over “mysticism” and the proclamations of mediums. He was in many ways the skeptical believer.

Under Bundy’s guidance, the Religio-Philosophical Journal deviated somewhat from its previous path. He believed it wasn’t enough to just write about the interesting incidents which stumped the scientific world. The journal now exposed frauds and hucksters regularly, condemning the showmanship and trickery of séances, trying to weed out the charlatans and conmen from those willing to attempt to prove their own abilities. Though unpopular in many Spiritualist circles, Bundy continued his “mighty work in elevating the tone of our own people, raising the moral sentiments, and breaking down of idol worship and all superstitions that fattened among us heretofore.”

Bundy paid the price for his skepticism. Financial trouble plagued him and the journal until his death in 1892. In the August 9, 1892, article on his death in the Chicago Inter-Ocean, a reporter honored him as “one of the keenest and coolest investigators of the phenomena of spiritual existence, and no disbeliever in Spiritualism was more feared by the tricksters who professed to be mediums than this man who frankly acknowledged himself as a believer.” The journal continued under the leadership of Benjamin F. Underwood until 1905. Underwood, who authored articles for Arena and the Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, was balanced between belief and skepticism (leaning more toward the latter) and maintained the integrity of the journal.

MORE GREAT STORIES FROM WEEK IN WEIRD:

You must be logged in to post a comment Login