Ask a Wizard: “Star Trek is an Occult prophecy?”

The Vicar was recently asked if Star Trek is part of some sort of Occult conspiracy.

The argument runs something like this: Eugene Roddenberry, creator of Star Trek, was a member of the Masons or other Illuminati-associated social club, and he was in contact with intelligence officers, military contractors, and psychic cult leaders who all pressed him to create and market a television program that would help remake the face of America and the world for centuries to come. Accordingly, he wove through the narratives of the original series (TOS) themes and symbols that would help predictively program Americans to accept a New World Order. We are also conditioned to accept the coming Great Conflagrations that will kill off most of the earth’s population, because the bright and utopian future of eternal frontier exploration is only possible as a result of the Eugenics Wars, the Third World War, and a post-war Mad Max-like apocalyptic era.

For some, this dovetails with Project Blue Beam. The purpose of Project Blue Beam? To prepare us all to passively accept the rise of the Antichrist on Earth, of course.

For some, this dovetails with Project Blue Beam. The purpose of Project Blue Beam? To prepare us all to passively accept the rise of the Antichrist on Earth, of course.

So goes the argument. But it is based upon nonsense and mist, and it fails to take into account – even from a speculativist perspective – that Eugene Roddenberry was never a member of any Illuminati cult. And he would not have welcomed the NWO as it is currently conceived of. Rather, Eugene Roddenberry was using an entirely different sort of Magick to achieve very different goals. The Vicar will make no claim that Roddenberry was a member of any specific mystical order – primarily because the reader is intelligent enough to draw her own conclusions, particularly with regard to a man whose television program taught us that Apollo was just a really simple-minded alien with incredible telekinetic powers.

ADVERTISEMENT

No, Star Trek is not an Occult prophecy. It is also not predictive programming of the sort its End-Times detractors assert. Nor is it a prong in the Project Blue Beam initiative.

Stark Trek is instead, a blueprint. As to where Roddenberry got that blueprint, it’s anyone’s guess. Occam’s Razor and the Skeptoids will demand that the whole enchilada was prepped and cooked by the creator and his production teams, writers, directors, producers and even sometimes the actors themselves. We can also readily identify that the stories and ideas behind Star Trek are like those emergent in any great work of fiction: Sometimes the characters write themselves, and the stories unfold according to their own logic and reality.

Perhaps this outlook is the most comfortable, but it fails to account for certain things. On the surface, these are small, but the corresponding implications are what should convince the truly open inquirer that something more may have been going on in the Burbank area in 1966.

Star Trek is a Utopia… Only it isn’t one.

Point the first – our supposedly utopian future is nothing of the sort. There is a deliberate balancing in the storytelling of most TOS episodes that demonstrates that while we are looking at the best-of-the-best on the Enterprise bridge, even Starfleet has some bad apples who go space-crazy or become drunk with power-lust. The overarching view is that people cope differently in the future, but that there are still extremes of behavior and acts taken in desperation. This is a great way to inject realism into a story that is about as far out as possible in most cases, but it also departs from the path of most science fiction that focuses on social commentary. It is clear that social commentary drives the Trekverse writers in many cases, because this is the tradition established by Roddenberry: Use the Trekverse as a vehicle for telling people how to live.

A utopian tale can do that, typically because the tale ends up being about the dystopia that was right in front of the reader all along, masquerading the whole time as some sort of paradise. But Star Trek is about showing us an achievable future that is less fiction and more reality. The starships are crewed by people in a quasi-military hierarchy. The equipment and technology are described in recognizable terms and are at least generally based on scientific theories and ideas. Multicultural melding is well underway. Starfleet is like a non-military space navy that sometimes still blows shit up. The institutions and character types tend to be recognizable. The themes are sometimes brutally obvious and absurd, but perfection is never asserted. The societies that gave rise to Roddenberry’s fictional Federation never intended a utopia. They intended a real-universe solution to real-universe problems that echo our own geopolitics, economics, and socio-cultural challenges. This is not pie-in-the-sky optimism. Gene was serious. You can build this.

The argument Roddenberry was making is simple enough on the surface: In the future, people are better. Humanity continues to get better as we go. But the society is not perfect. It needs perfecting; it requires people to continue forward, seeking the best solutions.

It’s what’s underneath the argument that is truly bizarre. How did people get better?

Star Trek is entirely about technologies we’ve never even imagined.

Society itself is a technology in Roddenberry’s future. People are being manipulated, conditioned, and trained in ways and to levels of efficiency that are frankly scary. The uplifting message is that we use these methods of acculturation for good in the 23rd Century. Whether we would do so in reality is another question entirely. But consider the characters, their roles, and the system that would have to exist to get all of the moving parts working together and make people act the way they do. Is the behavior of characters in TOS conditioned by drugs? Genetic modifications? Some kind of educational technology that enhances recall and retention? How are major mental illnesses handled?

Did narrative demands create a cast of carefully balanced characters? Or was Gene in the background, making sure that the ideal model was presented for balancing out a command structure to give it heart, intelligence, humanity, and technical know-how? Try this model yourself the next time you start a business or manage an operation. I’ll bet it works very well indeed.

Insubordination and emotional outbursts are rampant in TOS. I recognize that much of the reason for this is that it makes for good television. But the fact is that the incredibly flexible discipline of Starfleet is a clearly intentioned message of the show. People are allowed to blow up, and then go right back to work when they demonstrate that they are over it. People apologize to each other often openly, on their own initiative, and with full acceptance of responsibility. Are these things unheard of? No, of course not, and the 1960s are perceived as a more polite time than our own, in terms of casual social dynamics. But these things are unnaturally stressed in plots that do not require them to even be a part of the story. And they seem a little goofy under some of the circumstances in the narratives. Moralizing? Or fleshing out the blue print?

Based upon the personalities of the captains and top brass we get to see in TOS alone, it is obvious that Starfleet thinks narcissism and antisocial thinking are essential traits for leadership. Good captains follow the rules and only break them in extremity. Great captains re-write the rulebook entirely. Carefully watch the good officer characters, and we see that their somewhat criminal personalities are held in check by concerns for other people and particularly for those under their command – there’s a desire to be special and “the best,” but only through bearing the true burdens of command. A values system overlays the thinking of Kirk, who is about half-space-pirate on his best days. The systems used to train and acculturate people cause natural inclinations that in our day yield major problems, to instead be channeled into useful professions in the 23rd Century. We know what to do with the kinds of personalities that in earlier eras spread war and crime and corruption. We give them starships.

The copious lack of poverty and internecine strife suggests that these cultural management and educational systems are widespread and amazingly effective, as well as based upon a post-scarcity economic model. They are the reason behind the extremely weird behavior and social conventions observed by characters throughout the run of TOS. There’s a lot of calm, almost wooden reaction to fairly scary shit that has to be a function of direction, given the penchant of era-talents for campy overacting. Is everybody on space-Xanax? Or is there some other mechanism at work?

It is the social technology that matters most, and we do not generally think of society as a technology now, nor was this the common view in 1966. The idea of society as a workable tool that is subject to fine-tuning, rather than a thing that happens organically, is a vision of a technology we’ve never even imagined. General theoretical propositions abound in the works of our philosophers, heads of state, and political theorists, but an articulated system has never been proposed and precisely matched. Yet Roddenberry hints tirelessly that he has a perfect method, an ideal approach. But he will only show us the output, never the machine in its entirety. A hint here, a hint there…

I cannot describe this social technology, because it makes absolutely no sense when its output is observed. But I know that it exists because the detractors of the show will often point to patent behavioral absurdities in many episodes as indications of bad writing, sloppy production work, and weirdly wooden acting suitable only for a mid- to late-60s space opera. Only, that’s clearly not what was going on. Oftentimes, the “bad acting” and the “weird writing” fit into a scheme of overarching values and themes that run throughout the length not only of TOS, but also all subsequent films and iterations of the franchise. The weird behavior of the characters is a constant, not a variance. Reactions in TOS do not make sense from the standpoint of the time in which they were written, nor even in our own time.

What’s so weird about the characters in the Trekverse?

Where do I start? In The Man Trap, a shape-shifting salt-vampire gets waaaaaay too far in its infiltration of the Enterprise simply because the general level of suspicion and reactivity of the crew is so inhumanly low. Characters keep encountering the creature acting weirdly in different forms, and they make no attempt to intervene. Bad writing? One instance, or a few instances in isolation over the course of a series, and I would certainly agree. But this is the actual and obviously intentional message of the show’s social technology argument: people from the Federation are rarely reactionary or counter-productive. They are usually supportive, open, and inquisitive. When we see negative examples, they are presented as such, and reacted to by other characters as though they are a rarity. It is almost as though everyone has extensive training in counseling psychology and group dynamics.

There is almost no concept of punitive justice, and when retributive goals are raised, it is generally only as an example of how a justice system can go awry. In the episode Charlie X, a 17-year-old boy with godlike powers comes aboard the Enterprise. When he has a predictably adolescent response to Captain Kirk’s beautiful personal Yeoman, Janice Rand, crazy stuff starts to happen. People blink out of existence, turn into lizards, lose their faces, and uncontrollably spout poetry. Charlie threatens the survival of the crew by taking control of the ship’s systems. Even before Charlie’s powers are revealed, some of his inappropriate behaviors land him in the 23rd Century equivalent of “trouble”. This boils down to Kirk playing father figure to him, telling him about how to pick up chicks before teaching him some space-Judo.

The essence of Kirk’s lesson? You have to be gentle, and you have to learn how to fall before you can learn how to fight.

The essence of Kirk’s lesson? You have to be gentle, and you have to learn how to fall before you can learn how to fight.

After much havoc, some floating, wavy, green space ghosts show up and take Charlie back home, since he obviously cannot live among his own kind. And the reaction of the crew? They are deeply conflicted, wanting clearly to forgive Charlie and help him find a way to live among them. The level of openness and forgiveness is not at all what we might expect in a modern sense. Do things like this happen in our world? Yes, sometimes we want to forgive dangerous criminals. But dangerous adolescent boy-gods with some seriously inappropriate behaviors? Charlie wasn’t endearing. He was a psycho tyrant. The 23rd Century response is nevertheless, to forgive.

Trekverse science isn’t science in our terms at all. The exemplar of science and reason is the iconic Mr. Spock. Consider, just briefly, how widely this fictional alien personality is known, and you have awakened to the use of magick by a true master. The marriage of talents in the creation of just this one character is an alchemy more powerful than any occult worker can hope to produce. And how does Spock view science?

He’s a speculativist. A magick-user.

In Charlie X, Spock tells us that Charlie was marooned on an essentially dead planet at the age of 3, and somehow survived for 14 years alone on the surface. He then says that there is a legend of noncorporeal intelligences called Thasians originating from that planet. The legend is believed generally to be groundless, and McCoy champions the skeptical view – one cannot assume a myth to be true. Spock – computer-like, super-sciencey Spock – tells us that the mere fact that Charlie survived in these unlikely circumstances demonstrates that the legend is true. Only through some sort of intervention could the boy have survived, and only the mythic beings described as Thasians could have the power to conceal their existence so perfectly that they are thought to be the stuff of legend. Spock’s argument for the validity of the Thasians is like one of my arguments for the existence of Bigfoot – they must exist because some evidence is suggestive that they do exist, and anyway they are way better at hiding than we are at finding.

That’s not science. Skeptical Trekkers must squirm when they catch what Spock is saying. He defends his view as logic and science, but it is obviously the viewpoint of the future, and of an alien culture to boot. He’s talking like a wizard. After all, a Wizard assumes yes rather than assuming no, if only because yes is at least a positive and active frame of mind.

When Khan awakens in sickbay in Space Seed, he steals a surgical blade from a display and moments later seizes McCoy by the throat, threatening to slice him up. McCoy goads Khan on, giving him sound medical advice on where to make his incisions. This reverse psychology routine works even on the eugenic superman, who relents, saying, “I like a brave man.” Point for McCoy. Does Khan end up in the brig or restrained and kept in an induced coma? Of course not. Instead, about five minutes later the command crew is having dinner with Khan as the guest of honor. What? Why?

Some say shoddy writing and silly plots, with simplistic devices. But the writing that creates the Trekverse is actually pretty good. It discusses important topics in an interesting way, mingling adventure with psychological and moral explorations. This blend is brilliant. It means also that the behavioral mechanics in the plots are deliberate: they are the result of an advanced understanding of how to manage human beings for maximum realization of potential. You invite Khan to dinner because he’s a primitive military dictator. It’s what he expects. The “superior being” wants this kind of treatment; he demands it. And Khan actively observes and breaks down these tactics, without being able to counter their effects. In a very balanced, skillful bit of pop television nonsense, we are shown how to neutralize a monster.

Behavior taught through metaphor may be the oldest form of social technology.

And how, later on, do we punish Khan? Do we kill him, or send him to Earth to stand trial for 200-year-old crimes? No, of course not. Instead, we give him and his “superior” fellows a whole planet. How do we punish the Starfleet Historical officer (MacGuyver, is it?) for her plain acts of treason in assisting the old war criminal in his bid to take over Kirk’s ship? She gets to settle down with her new superhuman boyfriend and his buddies. Retribution is not a 23rd Century agenda.

What the blueprint means.

The people of the Federation appear to have laws through freedom, rather than the traditional options of freedom from or through laws. This is an idea so revolutionary, it is difficult to articulate. Somehow, the body politic is calmer, more rational, more problem-solving in its orientation. Somehow, the freedom of all is the law that governs the society. Basic needs are met, comfort is achieved. Now, on an endless frontier, what will you do with yourselves?

Consider Tomorrow is Yesterday, an episode about covering your tracks when you make a series of poor navigational and operational choices with respect to non-linear temporality. A pilot (Roddenberry was a pilot, and a combat veteran of the Second World War) is beamed aboard the Enterprise to avoid killing him when the ship’s tractor beam starts to tear apart his fighter. A 1960s UFO headline trope becomes the topic of a whole episode, which demonstrates that people from the future space navy can travel in time, but generally make far too many mistakes to get away with it on a regular basis. They have just enough technological advantage to manage to make it appear as if they have never been there while making good their escape back to their own time.

Consider Tomorrow is Yesterday, an episode about covering your tracks when you make a series of poor navigational and operational choices with respect to non-linear temporality. A pilot (Roddenberry was a pilot, and a combat veteran of the Second World War) is beamed aboard the Enterprise to avoid killing him when the ship’s tractor beam starts to tear apart his fighter. A 1960s UFO headline trope becomes the topic of a whole episode, which demonstrates that people from the future space navy can travel in time, but generally make far too many mistakes to get away with it on a regular basis. They have just enough technological advantage to manage to make it appear as if they have never been there while making good their escape back to their own time.

Did Roddenberry get picked up by aliens at some point? Did he receive messages? Was he pre-conditioning us for the horrors that lie ahead, in the hope that a visionary future would be the end result? His shows are rife with the notions of alternate universes and time travel and the ability of advanced societies to operate without the knowledge or even suspicion of less advanced cultures. In fact, it is Roddenberry’s show that has popularized the notion of a non-interference clause: The Prime Directive. Did Eugene know something the rest of us didn’t?

In Magick, we utilize counterforces. If I say, “It is forbidden,” my student will become curious. If I say, “No advanced civilization is interfering with us, because it is against the rules,” some will suspect that it isn’t so, and begin searching for evidence of interventionalism. Who is writing our news? Who is making our physicists develop the theories and equations they think are their own?

In a sufficiently vast universe, paranoia is merely reasonable suspicion.

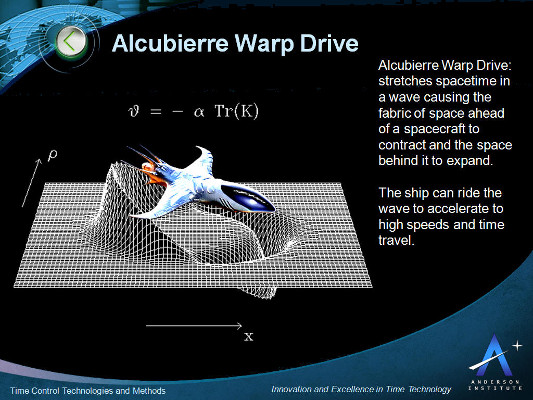

You have a cellular phone. You in fact have a smart phone with touch-screen tech that rivals Next Generation Trek in its abilities. These devices are communicator and tricorder in one – though they still cannot actually do what the devices in even TOS could do. All of that clunky, solid state technology they seemed to have actually had to have far more massive power cores and transmitting mechanisms than we can even imagine – they could talk to & see each other in real time from hundreds of light years away. By contrast, you have a lap top. But the lap top wants to one day be Kirk’s desk computer. Medical technology marches increasingly in the direction of the weird stuff McCoy thought of as old hat. Synthehol is a thing. Floppy disks were once a thing, too, although if you watch carefully, the pastel colored squares that TOS characters plugged into computers recorded data by being spoken to. That’s not something we can do yet – Dragonfire notwithstanding. And a man named Miguel Alcubierre says warp drive is possible. NASA has a project running now to test the theory on infinitesimally tiny levels. Follow the blue print.

Here’s a proposed Alcubierre Metric-based ship. Impossible – under current technology.

And, it looks nothing like the Enterprise. Except the real serious Trekkers out there will already have realized that the sci fi ship’s warp nacelles are filled with coils that do what the single toroidal shape in the ship above does: They warp space time, contracting it in front of the ship and expanding it behind. Shrink the shape above and link several in series for enhanced effect, and you have the core of those tubes hanging off the back of one of the most iconic ships in the history of science fiction. Why is that? Is it because Roddenberry met future men on a “Federation Starship” and snuck glimpses of the truth into the plots of a pulpy space adventure? Or is it because he mixed the right forces to produce a mystical effect, called a compelling in the business, and the result is predictive programming? Did the CIA do this? Or did one intrepid writer with a vision do this? Who inspired Alcubierre?

And, it looks nothing like the Enterprise. Except the real serious Trekkers out there will already have realized that the sci fi ship’s warp nacelles are filled with coils that do what the single toroidal shape in the ship above does: They warp space time, contracting it in front of the ship and expanding it behind. Shrink the shape above and link several in series for enhanced effect, and you have the core of those tubes hanging off the back of one of the most iconic ships in the history of science fiction. Why is that? Is it because Roddenberry met future men on a “Federation Starship” and snuck glimpses of the truth into the plots of a pulpy space adventure? Or is it because he mixed the right forces to produce a mystical effect, called a compelling in the business, and the result is predictive programming? Did the CIA do this? Or did one intrepid writer with a vision do this? Who inspired Alcubierre?The prophets of science fiction all have had profound impacts. But none lay out so clear a blueprint for so naturally derived a reality. It is not at all hard to believe that a future unified earth culture would mingle the justice system of the U.S. in its prime with the socioeconomic ethics of an idealized communist state with the respect for order of the Romans [references to Rome permeate the series] and the profound liberty of the colonial frontier. The elimination of widespread belief in religion has transformed the political landscape, yet people still have faith and hope and not a few indicate a belief in a great cosmic mind of some sort: perhaps the “Great Bird of the Galaxy.” They elect leaders, but scandals and corruption are mostly gone. There is no money. There is only the quest for self improvement and the voyage of discovery. Being a starship captain is a big effing deal. You make the papers and the pages of history, all while living in a paperless age. That’s a neat trick.

What Trek does that no other science fiction does at all is seed thinkers with certain key ideas as functions of a coherent and dynamic philosophy. This is the essence of magick as many others have rendered it: Predictive programming via fundamental paradigm shift. That kind of language always sounds bonkers and too field specific to me, though. It’s a matter of personal preference, but we must also respond to the demands of the language of our times.

Magick changes how you think about the world. Good magick makes it better. Bad magick makes it worse. Magick adds awareness of external forces to your life; you can now see that there might be a variety of noncorporeal entities around you at any given time, making gravity a thing, and making bananas turn brown. There must be invisible hands guiding the strings that we can see and count. I’m excited for everybody that there are atoms and shit, but the atoms aren’t the end of the discussion, and neither are so many higgs-bosons and quarks and tachyons. We can only run for so long from the realization that our entire universe – animate and inanimate parts alike – is a living thing. More correctly, it is a collective of living things, each with unique intelligence and purpose, that together equate to far more than the sum of the parts.

There is indeed a conspiracy behind Star Trek, but I lay it at the feet of its creator. Perhaps through some wizardry, or some alien contact, or some governmental black project, the show was conceived to compel certain types of people. This has led directly to revolutions in technology and obsessions with certain scientific pursuits. Many things inspire. Many things have had a profound impact over time. But this is in fact the essence of the argument: Such a thing that has so great an impact so quickly begins to test the boundaries of credulity. Real life things with serious impact and implications are actively being invented and pursued because of Star Trek.

Mr. Spock might suspect some alien influence.

To the conspiracist that sees only dark powers at work behind the scenes, it is important to remember that the mystery of alchemical work is not found in compounds and mixtures. It has always been in the mingling of forces. Outcomes show the way to processes in magick. I know that isn’t actually a logical statement, since we cannot reasonably innovate when we do not know that we are even capable of doing the innovation. But this is the reality of magick, and why it is not for the faint of heart or the sure of mind. “The fool makes the finest hero.” If we emulate the abilities of UFOs that we have never yet proven real, are we crazy, or inspired by genius?

Did the UFO really exist? Or was it a light show, a flare, a penlight wielded by some capricious child-god drifting by on her cloud?

Sometimes, there are good guys using magick for good reasons and getting good results. It’s the stuff that makes us think – long and hard and always second-guessing and rearranging – that really matters. And if I was an alien with an agenda of manipulating a species’ development, I think I’d start with the things that they pay the greatest attention to… Doctor Who, anyone? Or Shakespeare, for that matter, whom Doctor Who itself once implied was “inspired” by alien influences. If I were an order of wizards charged with bringing out the best in humanity, I might try getting something on the T.V.. If I was a science fiction writer with an inspired vision of tomorrow, my choice of venue would be pretty obvious.

What do you pay the most attention to? What is the best way to change your way of looking at the world?

Follow the blue print. It means more than we yet realize. In Riverside, Iowa, there stands today a monument depicting the town as the future birthplace of James T. Kirk. A space shuttle was deliberately named after the fictional starship, and now has in turn been absorbed into Roddenberry’s canon. A physicist decided he could make warp drive happen, and the idea appears to have legs. Something is happening here. I can’t tell what force is at work or what process is driving it all forward, but something is definitely happening.

So follow the blue print. Gene dares you.

So follow the blue print. Gene dares you.

MORE GREAT STORIES FROM WEEK IN WEIRD:

You must be logged in to post a comment Login