By now, it’s a well-accepted fact that the Vikings beat Columbus to the New World (i.e. North America) by a couple hundred years. Settlements have been found in Newfoundland along the Eastern Canadian coast. But exactly how far south they traveled in North America is still a mystery. But could a buried warrior and a strange stone hold the key to the mystery, or is it just the tip of an archaeological iceberg?

Fall River, Massachusetts, is perhaps best known for the violent double homicide leading to the murder trial of Lizzie Borden, but 50 years before that crime, the town was made famous by another shocking headline. Near the present site of New England Gas Company where 5th Street meets Hartwell, workmen excavating a hill uncovered a skeleton in a shallow grave in 1831. According to a contemporary account published in 1839 for American Monthly Magazine, the skeleton was buried in a sitting position encased in coarse bark with its head one foot below ground level. It appears the young man had possibly been mummified either naturally or intentionally (“The preservation of this body may be the result of some embalming process, and this hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that the skin has the appearance of having been tanned…”) and wrapped in a coarse cloth resembling burlap. He wore a large brass breastplate across his chest, and around his waist was

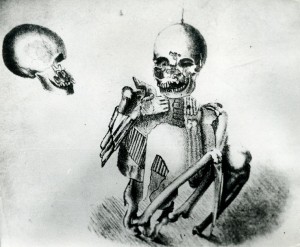

Original sketch of the Skeleton in Armor republished in 1953 by the Fall River Herald News.

“…a belt composed of brass tubes, each four and a half inches in length and three-sixteenths of an inch in diameter… the length of the tube being the width of the belt. The tubes are of thin brass, cast upon hollow reeds, and were fastened together by pieces of sinew… The arrows are of brass, thin, flat, and triangular in shape, with a round hole cut through near the base. The shaft was fastened to the head by inserting the latter in an opening at the end of the wood, and then tying it with a sinew through the round hole, a mode of constructing the weapon never practiced by the Indians…”

There is some historical debate as to the last statement. Brass was not unfamiliar to native tribes who had been known to trade goods for brass kettles which they melted down for arrowheads and adornments in the 1600s. One brass tube was donated to Copenhagen’s Peabody Museum in 1887; analysis revealed it was indeed brass. Without modern dating techniques, though, the age of the skeleton couldn’t be determined. Some people insisted it was some lost Indian chief. Others suggested it was undoubtedly Phoenician and proved that some forgotten Mediterranean peoples had crossed the Atlantic and formed the mythical Atlantis “beyond the Pillars of Hercules” (or Rock of Gibraltar) as recorded by Plato. Others insisted it was just a hoax.

ADVERTISEMENT

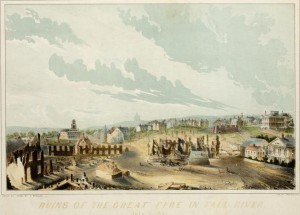

The remains and artifacts were carefully excavated and placed on display at the Fall River Athanaeum. Unfortunately—or curiously, as some have pointed out—the museum housed in the old Town Hall burned to the ground in the Great Fire of 1843. The famed “Skeleton in Armor” was destroyed, and his true identity forever lost by unceremonial cremation. Yet his story lived on through the poem “A Skeleton in Armour” published in 1841. Its author, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, made an entirely different bold claim:

“I was a Viking old!

My deeds, though manifold,

No Skald in song has told,

No Saga taught thee!

Take heed, that in thy verse

Thou dost the tale rehearse,

Else dread a dead man’s curse;

For this I sought thee.”

Whether Longfellow truly believed the skeleton was Norse (and that the Norse were also responbibsible for construction of Newport’s Old Stone Mill) is still uncertain, but he was likely influenced by Danish historian Carl Rafn who published Antiquitates Americanæ—a large body of his work related to early Viking exploration in North America before Columbus—in 1837. Norse writings told of land west of Greenland they discovered and explored. They called it Vinland, translated by some historians as “Wine Land”, so named for its abundant grape vines. Finally in the 1960s, archaeologists began to unearth the first definitive proof of Norse settlements along the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, at Jellyfish Cove (or L’Anse aux Meadows). There is some ongoing debate as to whether Vinland referred to grapes or meadows. Some archaeologists speculated that this settlement was indeed Vinland, while other researchers feel that the name implies that the Vikings traveled much farther south into New England where wild grapes would’ve been found in abundance.

But there’s another puzzling piece to the mystery, from just a few miles north of Fall River on the Taunton River. It’s called Dighton Rock, and some people believe it’s further proof of the Norse in Massachusetts.

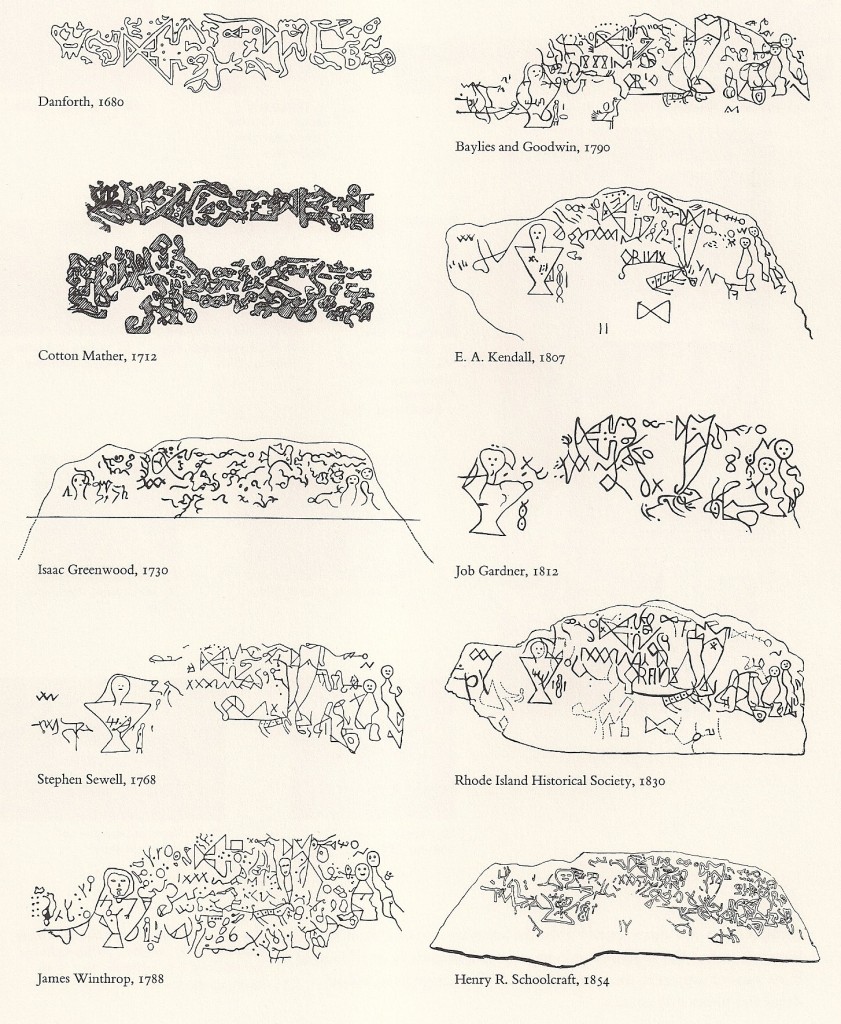

Since the late 17th century, the strangely carved boulder known as Dighton Rock has been a great curiosity and point of controversy. No one can be sure of how long it had been endlessly flooded and uncovered by the tides when John Danforth first sketched the strange pictographs in 1680. Though many attempts have been made to pinpoint an exact telltale calling card to tie it in perfectly with a specific group of people, even the best evidence is highly questionable. Explanations range from Native Americans documenting the first white settlers to the Ancient Chinese to Portuguese explorers landing there in 1511. And yes, of course, even the Vikings.

Carl Rafn believed these inscriptions were Norse in origin, perhaps telling of a voyage by Leif the Lucky in 1000AD (which fed right into Longfellow’s poetic, romantic interpretation). But he’s not the only one to have fanciful ideas behind it. Count Antoine Court de Gebelin of Paris declared that he had uncovered its secrets in 1781. It was, according to him, a testimonial from a ship crew who had traveled there from Carthage in ancient times and told the natives of their perilous voyage. A Harvard scholar named Samuel Harris, Jr., claimed to have found the Hebrew words for “king”, “priest”, and “idol” inscribed on the stone in 1807. Twenty-four years later, Maryland teacher Ira Hill announced that it was documented proof of a biblical voyage from the Old Testament:

“And King Solomon made a navy of ships in Eziongeber… And Hiram sent in the navy his servants, shipmen that had knowledge of the sea, with the servants of Solomon. And they came to Ophir, and fetched from thence gold, four hundred and twenty talents, and brought it to King Solomon.” – I Kings 9

How could so many ideas come from one stone? Just look at the differences in transcription of the stone between 1680 and 1854.

Weathering isn’t the only impact the rock has received over the years. As seen on the changing inscriptions, there has been evidence of vandalism over the centuries. One possible written text over the petroglyphs could be translated to read “Injun Trail to Spring in Swomp → yds. 167”, implying directions written after 1680 by (somewhat) literate settlers. Perhaps the most important point about Dighton Rock was made by Professor Edmund Delabarre of Brown University. After discrediting the Viking theory of the stone’s origins, he suggested that psychology could hold the key to the perplexing number of theories about the stone. For him, it was all a matter of psychic projection—similar to the Rorschach test, each examiner is taking these simple scratches and imposing their own opinions onto the stone. He concluded that the pictographs were most likely made by native tribes and their meanings corrupted by people having their own agendas and visions for what history might have been.

While we can’t say that an armor-clad skeleton lost in a blaze or carved symbols on a weathered stone say for sure that Vikings landed in New England, it still remains a theory that tantalizes rogue archaeologists. For all we know, they did see the shoreline of Massachusetts a thousand years ago, but it will take much more than a worn puzzling stone or brass tube to prove it. Still, both the Skeleton in Armor and Dighton Stone remain puzzles yet to be completely unlocked.

MORE GREAT STORIES FROM WEEK IN WEIRD:

-

Advertisement

Subscribe for the latest Weird News Delivered Daily!

Join the world’s only mobile paranormal museum!

World’s Weirdest News in your Social Feed!

Latest Stories

Phenomenacon: Attend the World’s First Online Paranormal Conference, Featuring Your Favorite Paranormal TV Stars

Martin Nelson | 04/22/2020With the onset of a global pandemic causing the shutdown of fan conventions all over the world, it was only a matter of time before the cancellations hit the...

7

Groundbreaking Paranormal Documentary Series “Hellier” Returns with Ten Haunting Episodes of Appalachian Mystery

Martin Nelson | 11/28/2019There’s something strange moving through Kentucky like a virus, twisting through the Mammoth Cave system and hovering in the skies above the Appalachian Mountains. While might catch glimpses of...

7

Travel Channel’s “Haunted Salem: Live” Features the “Paranormal Dream-Team” in Live, Four-Hour Ghost Hunt

Martin Nelson | 09/27/2019Travel Channel is kicking off Halloween season on October 4th with a very special live event that brings together more of the network’s top paranormal stars than you can...

7

Meet Devin Person, a Real-Life Wizard Who Grants Wishes on the New York City Subway

Greg Newkirk | 06/11/2019For most of us, ignoring the strange people on the subway is second nature, but if you ever find yourself in the tunnels below New York City and you...

7Stories from Around the Internet

#PLANETWEIRD ON INSTAGRAM

About Week in Weird

Week In Weird is one of the web's most-visited destinations for all things weird, bringing you the latest fringe news, original articles featuring real investigations into unexplained phenomena, eyewitness reports of encounters with the anomalous, and interviews with notable figures in the fields of extra normal study.

Week In Weird is part of the Planet Weird family, brought to you by the paranormal adventures of Greg Newkirk and Dana Matthews, professional weirdos investigating the unexplained by engaging the strange.

- MORE ABOUT WEEK IN WEIRD

- REPORT A SIGHTING / CONTACT

- ADVERTISE WITH USFOLLOW PLANET WEIRD ON TWITTER

GREG & DANA: INVESTIGATING THE UNEXPLAINED

Content copyright © 2016 Planet Weird unless otherwise noted.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login